My first exposure to a dragon drawn from folklore was most likely Smaug, the red-golden dragon in J. R. R. Tolkien’s book The Hobbit. I remember being fascinated by his size, his jewel-encrusted underbelly, and the enormous treasure he guarded. Although he is a fictional creation, the inspiration for Smaug comes from Scandinavian folklore.

I laughed when I opened the book and saw that I had written my name twice in the interior. (Pollycutt is my maiden name.) I guess I wanted to make extra sure that anyone who borrowed the book would know who it belonged to. 😉 I think I was around twelve years old when I received and first read the book. Do you have a favorite dragon?

Dragons have a lengthy history in folklore and literature. While their origin is uncertain, stories of dragons exist in many places in the world, both in the West and the East. And tales can be found in ancient, medieval, and contemporary literature alike. To keep with the theme of my blog, though, our focus will be on British and Celtic dragons.

This month we’ll look at the traits of dragons and discover a few legends about them. But while researching, I came across an interesting book, The Celtic Dragon Myth by John Francis Campbell, translated with an introduction by George Henderson. It has more than just dragons, though, and I thought it would be fun to explore it next month.

Characteristics of Dragons and Worms

“Dragon” and “worm” are often used interchangeably to describe these scaly creatures. Icy Sedgwick offers a nice explanation about these terms in her post, “Dragons in Folklore: The Lambton Worm and the Laidly Worm”:

The word ‘worm’ comes from the Anglo-Saxon word ‘wyrm’. This was a generic word and covered everything from Beowulf’s dragon to scorpions and snakes (Thompson 2014). It also came from the Old Norse word ‘ormr’ (Moon 2015). Over time, ‘worm’ and ‘dragon’ ceased being synonyms. Now, we’re more familiar with dragons, and worms are something you’d find in the garden.

British and Celtic dragon folklore stems from a Scandinavian influence. Many of these dragons are called worms and have slightly different characteristics than dragons. Katharine Briggs explains in her book, An Encyclopedia of Fairies: Hobgoblins, Brownies, Bogies, and Other Supernatural Creatures, that worms are “… wingless, generally very long, with a poisonous rather than a fiery breath and self-joining.” Yet in many ways worms are very similar to winged and fiery dragons. She writes:

Both are scaly, both haunt wells or pools, both are avid for maidens and particularly princesses, both are treasure-hoarders and are extremely hard to kill.

She also notes that in tales from the Scottish Highlands, worms are often found in rivers or the sea.

In a talk given by Joseph Nagy on “‘The Celtic Dragon Myth’ Revisited,” he explores a few more characteristics of dragons. He describes a dragon as “… a hybrid—part serpent, sometimes part fish or bird or terrestrial animal, and part sui generis.” And he adds that dragons “… are generated by and highly susceptible to transformation.” For example, they may start their life as a small larva or snake and change to a dragon over time or under certain circumstances.

Let’s look at some specific examples to see these characteristics in action.

Gwiber, a Flying Serpent

In many districts in Wales, there was once a tradition of flying serpents known as the gwiber. In Welsh Folk-Lore: A Collection of the Folk-Tales and Legends of North Wales, Elias Owen relates the origin of the gwiber. He explains that these creatures were once snakes, but “… by having drunk the milk of a woman, and by having eaten of bread consecrated for the Holy Communion, became transformed into winged serpents or dragons.” Like other dragons, a gwiber would attack people and devastate the countryside.

Owen includes a legend about a gwiber from a Mr. Hancock as described in his “History of Llanrhaiadr-yn-Mochnant” (published in Montgomeryshire Collections). In order to prevent a particular gwiber in Montgomeryshire from continuing to attack the area, a stone pillar was raised as a sort of weapon. Mr. Hancock explains how the pillar was used:

The stone was draped with scarlet cloth, to allure and excite the creature to a furor, scarlet being a colour most intolerably hateful and provoking to it. It was studded with iron spikes, that the reptile might wound or kill itself by beating itself against it. Its destruction, it is alleged, was effected by this artifice.

Apparently, the gwiber was thought to have two hiding places in Montgomeryshire, both known as Nant-y-Wiber. One was in Penygarnedd and the other in the parish of Llansilin. The stone pillar was believed to be in the gwiber’s direct line of flight between its two lairs.

The Dragon of Wantley

The Dragon of Wantley is a legend that includes a fiery dragon, a strong champion, and a maiden. Katharine Briggs offers a version of the tale, which was originally published by an anonymous author as a ballad. She begins in this manner:

This dragon was the terror of all the countryside. He had forty-four iron teeth, and a long sting in his tail, besides his strong rough hide and fearful wings.

He ate trees and cattle, and once he ate three young children at one meal. Fire breathed from his nostrils, and for long no man dared come near him.

As the legend goes, a knight of great strength, named More of More Hall, lived near the dragon’s den. The local people came to More Hall with tears of sadness and desperation, asking the knight for his help. If he would but slay the dragon, they would give him all of their worldly goods.

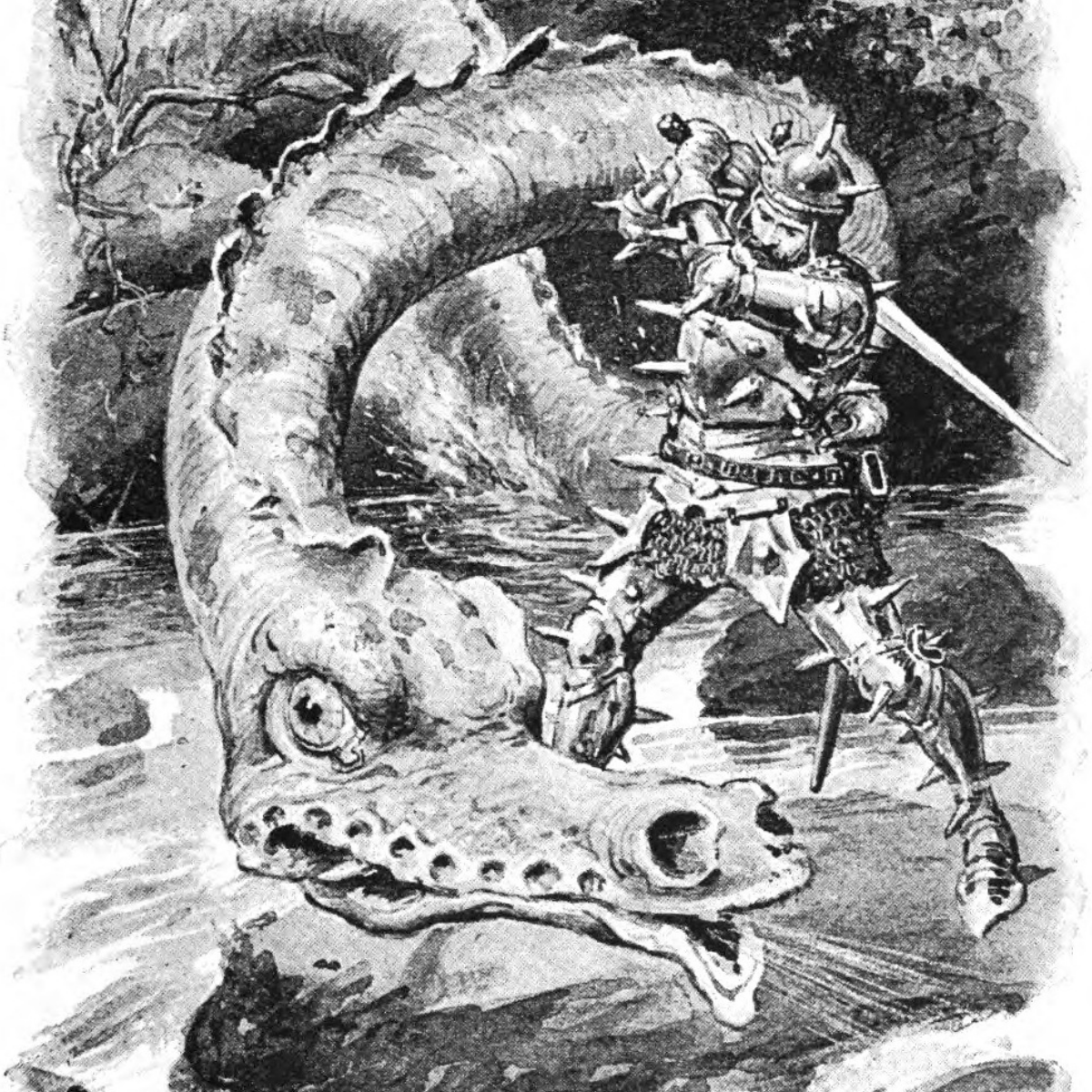

But More didn’t want their belongings. His only request was that a black-haired maiden of sixteen anoint him the night before and dress him in his armor in the morning to prepare him to fight the dragon. He then sought out a smith in Sheffield to make him a suit of armor.

The armor was set with steel spikes all over—on the front and back, on the arms and legs. Some spikes were five or six inches long! The ballad claims that the knight looked like a giant hedgehog and frightened all the local animals.

In the end, More used his wit rather than his strength to prevail. He climbed down into a well, and when the dragon bent to drink from it, the knight struck him in the face. A great battle ensued for “for two days and a night,” but neither one wounded the other.

Finally, the dragon attacked as if he would lift More high into the air, but the knight kicked him in the back, driving one of the iron spikes deep into the dragon’s flesh. The dragon spun and groaned, cried and moaned, then “… collapsed into a helpless heap, and died.”

The legend of the Dragon of Wantley interested me because not only does it display elements of dragon myth, but it also has inspired multiple literary creations, including the anonymous ballad, a novel, and even an opera!

The Lambton Worm

Similar to the Dragon of Wantley, the legend of the Lambton Worm embodies dragon folklore and has had a large cultural impact. It has given rise to a song, literature, film, and (wait for it) an opera! Until researching this topic, I hadn’t realized that dragon-based operas existed. 🙂

William Henderson, in his Notes on the Folk-Lore of the Northern Counties of England and the Borders, explains how this legend has become deep rooted in County Durham:

The Lambton Worm, partly from the romantic character of its history, partly because it relates to a family of note in the county, seems to have taken deep hold of the popular mind in Durham, and it is peculiarly fortunate in a chronicler. … Sir Cuthbert Sharpe … collected every particular respecting this Worm from old residents in the neighbourhood of Lambton, and placed the whole in the Bishoprick Garland, a collection of legends, songs, ballads, &c., relating to the county of Durham.

Henderson includes the legend in his book, but I was also able to locate The Bishoprick Garland. As the story is similar and quite long in both books, I’ll condense it into more of a summary.

One Sunday, the young heir of Lambton went fishing in the River Wear, instead of spending the day in solemn observance. He was not having much luck, and after shouting out curses in disappointment, he finally felt a tug at the line. But to his great dismay, he’d only caught a worm of unseemly appearance. So he flung it into a nearby well.

The worm grew and grew, and at some point no longer fit in the well. It took to resting coiled on a rock in the River Wear during the day and “twining” itself around a hill at night. It grew so large that it could wrap itself around the hill three times with its length.

The worm began terrorizing the area, drinking the cows’ milk and devouring lambs. With the young heir of Lambton off fighting in a war at this point, the old lord and household of Lambton Hall attempted to pacify the worm by offering it milk in a trough daily. And many knights came to fight it off, but without success, as the worm had the ability to reunite itself after being cut.

After seven years, the heir of Lambton returned to find the lands destroyed and the people overwhelmed. After seeing the worm for himself and learning that none had yet destroyed it, he consulted a wise woman to see what should be done.

She told him that he was the one who’d brought the worm forth to devastate the countryside. She advised him to cover his armor with spearheads and bring his sword to fight the worm on the rock in the river. She ended the discussion by making him vow to kill the first living thing he encountered after slaying the worm. If he didn’t, then no lord of Lambton would die in bed for nine generations.

So the heir of Lambton dressed in his spiky armor and went out to the rock. And much like a constrictor, the worm wrapped itself around the knight, essentially wounding itself against the heir’s armor. As the worm bled and lost strength, the knight gained the upper hand and cut the worm in two with his sword. The swift river water swept part of the worm away—keeping it from reuniting itself—and the worm was slain.

Victorious, the heir returned home and gave a blast to his bugle, the signal to the household to let loose a hound (a pre-arranged sacrifice to keep his vow). But his father rushed out to embrace him instead. He couldn’t bring himself to harm his own father, so he blew on the bugle again. The hound emerged, and he slayed it, but it was in vain. He’d broken the vow he’d made. Consequently, for nine generations, no lord of Lambton would die in his bed.

If you’re wondering if the curse came to pass, Henderson notes that while the exact date of the legend is uncertain, it is believed that the heir in the tale was Sir John Lambton, knight of Rhodes. He explains further:

Now nine ascending generations, from a certain Henry Lambton, Esq. M.P. would exactly reach to Sir John Lambton, knight of Rhodes; and it was to that Henry Lambton that the old people of the neighbourhood used to look with great curiosity, marvelling whether the curse would “hold good to the end.” He died in his carriage, crossing the new bridge of Lambton, on the 26th of June, 1761; and popular tradition is clear and unanimous in maintaining that, during the period of the curse, no lord of Lambton ever died in his bed.

Dragon Folklore is Often Local

While legends provide a way to learn about the characteristics of dragons in general, many of the tales I came across were linked to specific areas or a particular, local champion. Icy Sedgwick explains more about this in her post:

The stories become fables, praising the ability of the community to deal with a problem without recourse to outside help. They also embed the story within the local landscape, creating explanations for landmarks or strange features.

This seems to be true of the gwiber, the Dragon of Wantley, and the Lambton Worm. In each legend, it is the resourcefulness of the local champion or community which conquers the dragon.

As ever, thank you for reading.

Art credit (featured image): “He struck a violent blow upon the monster’s head” by C. E. Brock in English Fairy and Folk Tales (selected and edited, with an introduction, by Edwin Sidney Hartland) via Wikimedia Commons, public domain