One of the oldest aspects of European faerie folklore is the belief that faeries desire human children and often steal them away from their mortal parents, replacing them with changelings. Early changeling stories appear in medieval texts and continue through the 20th century.

Unlike fairy tales, stories involving changelings are considered to be legends: the accounts are tied to particular places and times, and they contain beliefs that were widely regarded to be true. As Terri Windling writes in her essay, “The Stolen Child: Tales of Fairy Changelings”:

Changeling stories are folk legends, usually set in the same country as the teller, and come from an ancient belief system in which fairies are real, co-existing with mortals.

The belief in changelings extended from Pre-Christian to fairly recent times (as late as the 1900s). Changeling stories often describe physical and behavioral changes in the child, leading the parents to believe that their child has been stolen by faeries and replaced with a changeling.

Protecting Children from Faeries

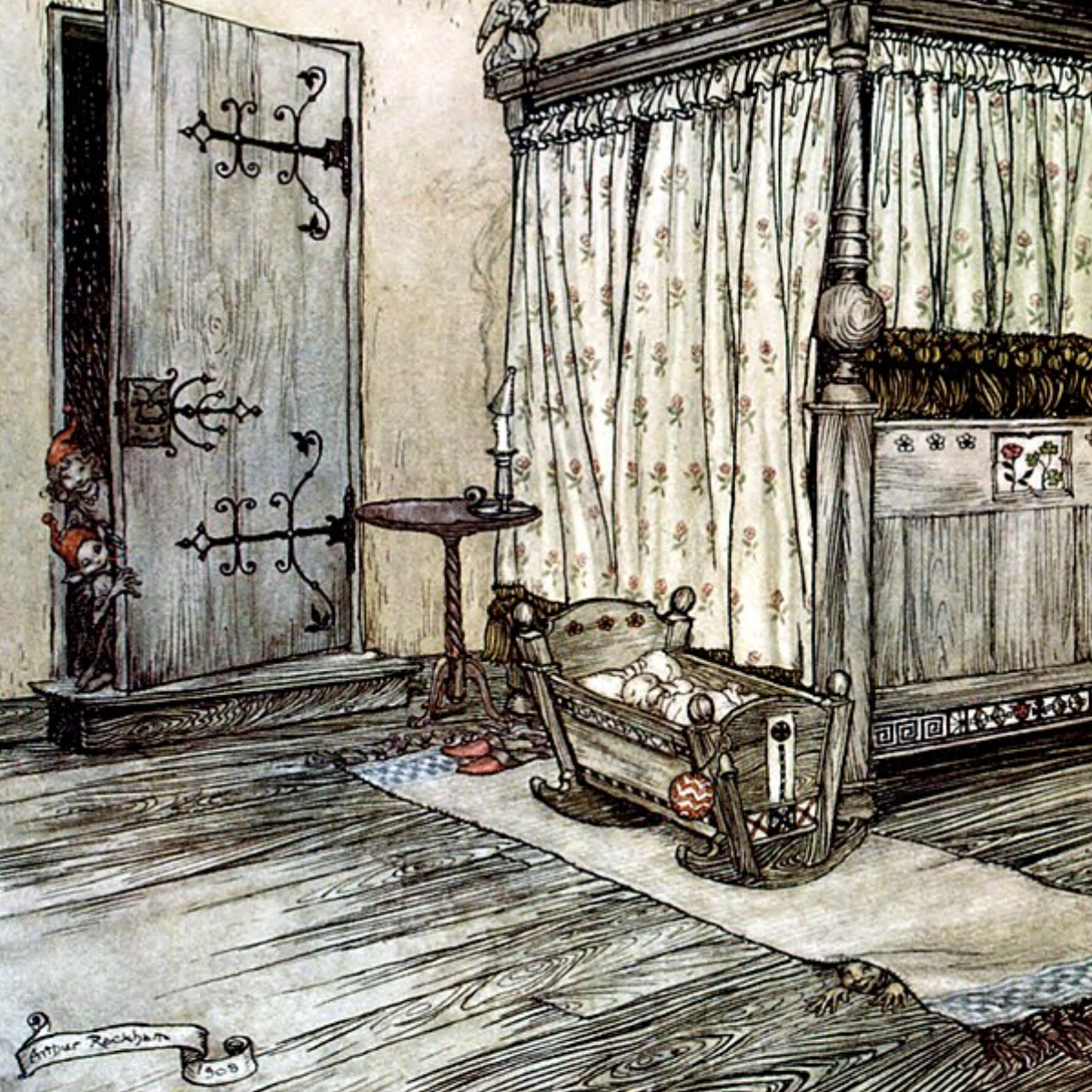

Children who were not properly protected from faeries were believed to be at the greatest risk of being stolen. Consequently, a variety of protection methods evolved to counter the faeries. While protections varied depending on location and time period, a frequently used form of protection included constant vigilance regarding newborn children. Parents and family/friends would continuously watch over newborns for the first three days of life, then continue a close observance of the child during its first six weeks.

Other protective measures included hanging an open pair of scissors above the cradle (but what if it fell?!), laying a piece of the father’s clothing on the child, or placing salt on the doorstep and windowsills. Baptism of the child was also felt to offer strong protection against faeries.

In spite of the protection options afforded to parents, children were still frequently believed to have been stolen by faeries and replaced with changelings. The folklorist Katharine Briggs explains in An Encyclopedia of Fairies that the “…true changelings are those fairy creatures that replace the stolen human babies.” The changeling served as a substitute child meant to trick the parents into thinking their child was still there, when really it had been whisked into the faerie realm.

Different Forms of Changelings

It is interesting to note that the changeling taking the place of the child could take different forms. The changeling might be a faerie child who did not thrive or an old faerie deemed to be of little use. In either case, the unwanted faerie would be left behind in favor of the human child.

Other times, the faeries might employ the use of a stock: a piece of wood the size and shape of a child and imbued with faerie glamour to make it appear life-like. Once the glamour faded, it would seem that the child had died and the stock would be buried.

Why Faeries Desire Human Children

Some stories suggest that the faeries were required to pay a tithe to the Devil every seven years and used human children to fulfill that requirement. Other tales reveal that mortal children might be brought into the faerie realm in order to strengthen faerie bloodlines. In some folklore traditions faeries simply prize the beauty of human children, and the desire to possess such beauty is the impetus for child theft.

Changeling Characteristics

Weight loss, lack of satisfaction with breast milk or food, extensive crying, and delayed or slow development were all considered characteristics of a changeling. With advances in medical science, we now understand that these symptoms were likely due to what is known today as failure to thrive. Johns Hopkins Medicine explains that failure to thrive can result from a medical cause (such as chromosome abnormalities, cerebral palsy, celiac disease) or from environmental factors (such as abuse, neglect, poor nutrition).

If parents discovered such changes as described above in their child and felt their child had been replaced with a changeling, the next step they would often take was to get advice about how to proceed from a third party (like a neighbor, relative, or church leader). The methods for ousting a changeling were often harsh, and people hesitated to take action without backing from their community. As D. L. Ashliman writes in his essay, “Changelings”:

In spite of the general credibility given to changeling accounts, and the support that they received from respected church leaders (Catholics as well as Protestants), there is evidence that many people were uneasy about the cruel treatment that the legends seemed to advocate.

Reclaiming Children from the Faeries

Changeling stories generally take a dark turn around this point in the tale. To encourage the faeries to return the true child to the parents, severe mistreatment of the changeling was often employed. (Please note, if child abuse is a trigger for you, click here to skip to the final section.)

As mentioned earlier, the changeling might be perceived to be an unwanted faerie child or perhaps an old, useless faerie. If the changeling was deemed to be a faerie child, the parents were advised to torment the changeling until the faerie parents came to take their own and return the true mortal child. Changelings were often gravely mistreated in these efforts—they might be thrown into water; left unattended in a field; beaten; or laid on a hot stove, griddle, or shovel.

Ousting a changeling that was perceived to be an old faerie required tricking it into revealing its true age (as old faeries typically pretended to be an infant or child). Katharine Briggs relates a common method for how this could be achieved in An Encyclopedia of Fairies:

It was to take some two dozen empty eggshells, set them carefully up on the hearth and go through the motions of brewing [i.e. brewing beer or stew in the eggshell]. Then the constant sobbing and whining [of the changeling] would gradually cease, the supine form would raise itself, and in a shrill voice the thing would cry ‘I have seen the first acorn before the oak, but I have never seen brewing done in eggshells before!’ Then it only remained to stoke up the fire and throw the changeling on to it, when he would fly up the chimney, laughing and shrieking, and the true baby would come to the door. Sometimes the child would not be returned and the parents would have to go and rescue it from the fairy hill.

Her words also point to the fact that in some changeling accounts the child is returned unharmed. In others, an extra step is needed, like going to the faerie hill to retrieve the true child. But in some tales, the changeling is ousted or killed, and the mortal child is never seen again. The last scenario reveals why parents sought out community approval before taking action against a changeling.

This begs the question, were parents ever held accountable for the mistreatment of perceived changelings? During the second half of the 1800s, there are court records which reveal defendants being accused of abuse and murder of changelings. And while there are some records of cases earlier than that, it is suspected that many incidents went uncharged or unaccounted for.

“A Pisky Changeling”

I’ll leave you with a short changeling tale, “A Pisky Changeling”, gathered by W. Y. Evans-Wentz from Mrs. Harriett Christopher for his book, The Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries. (Note that “piskies” is the name for West Country faeries.):

A woman who lived near Breage Church had a fine girl baby, and she thought the piskies came and took it and put a withered child in its place. The withered child lived to be twenty years old, and was no larger when it died than when the piskies brought it. It was fretful and peevish and frightfully shrivelled. The parents believed that the piskies often used to come and look over a certain wall by the house to see the child. And I heard my grandmother say that the family once put the child out of doors at night to see if the piskies would take it back again.

Art credit (featured image): Almost Fairy Time by Arthur Rackham via Wikisource, public domain