During the nineteenth century, folk songs were a vital part of daily life in Ireland and Scotland. Integrated into both work and play, songs eased the burden of chores and encouraged social interaction within a community.

In Old Irish Folk Music and Songs: A Collection of 842 Irish Airs and Songs Hitherto Unpublished, P. W. Joyce describes how folk music permeated his early life in County Limerick in the 1830s:

My home in Glenosheen, in the heart of the Ballyhoura Mountains, was a home of music and song: they were in the air of the valley; you heard them everywhere—sung, played, whistled; and they were mixed up with the people’s pastimes, occupations, and daily life.

I found his description relatable, as I had grown up surrounded by music of all types. We sang traditional songs in elementary school, which introduced me to folk music. I took piano lessons and learned to play classical music. My dad played guitar and sang old songs to my brother and I. My mom would play records on weekend afternoons. And whenever I had to do chores, I would listen to music to help pass the time.

As I began researching folk songs for this post, I soon came across work songs, which were sung while performing tasks or work. I was struck not only by the variety of tasks that included songs as part of the completion of the work, but also by the way the songs brought cheer and a sense of community.

If you also like to listen to music or sing while you work or do chores, then hopefully you’ll find the information in this article as interesting as I did while researching it. And you may even discover a new way to incorporate music into your daily tasks. 🙂

Songs for Daily Work in Ireland and Scotland

P. W. Joyce not only documented Irish folk music, but he also published books in the areas of history, folklore, language, and literature. In his book, A Social History of Ancient Ireland: Treating of the Government, Military System, and Law; Religion, Learning, and Art; Trades, Industries, and Commerce; Manners, Customs, and Domestic Life, of the Ancient Irish People, Vol. 1, he writes that Irish music included what he refers to as “occupation-tunes.”1

These “occupation-tunes” were songs that included lyrics and a melody that suited the work they were being sung to. They might have a special rhythm that went along with a specific task, or they might simply be associated with a particular occupation.

Joyce also notes that there is a strong connection between Ireland and Scotland when it comes to music. He explains that both Scottish and Welsh harpers learned from Irish harpers. He goes on to write:

It is not correct to separate and contrast the music of Ireland and that of Scotland as if they belonged to two different races. They are in reality an emanation direct from the heart of one Celtic people; ….

With this in mind, I will include examples of work songs from both Ireland and Scotland. And because of the link he mentions above with Wales (also a Celtic nation!), and the fact that I love all things Welsh, I will mention a few examples from there as well.

Rhythmic Task-Related Songs

Work songs that employed a rhythm to synchronize with the work itself were very common in Ireland and Scotland. For example in A Social History of Ancient Ireland, Joyce mentions “a ‘Smith’s Song,’ the notes of which imitate the sound of the hammers on the anvil.” Other tasks often accompanied by rhythmic songs included milking, churning butter, spinning, and rowing boats.

While researching, I came across an interesting article and video that describe Scottish waulking songs. These tunes were sung by women while they worked to shrink the cloth (tweed), a task known as waulking. Francis Collinson, in “Scottish Folkmusic: An Historical Survey,” describes how the song mingled with the work:

A group of about eight women sit round a table and pound the wet cloth on the table with their hands in time to the music of the song, with a series of movements which sends the cloth sun-wise round the table. It is this pounding which shrinks the cloth. The song is led by a soloist or leader who sings the verses of the poem; then the chorus joins in with a curious kind of nonsense refrain which keeps the music going and allows the leader to draw breath for the next verse, so that there is no break in the rhythm.

If you’re interested to see this in action or learn more about waulking, this video gives a good example.

Songs to Soothe Animals During Work

Some work songs helped to reassure the animals involved with certain tasks to stay calm and focused. There were songs to help with herding and driving cattle, as well as for milking and plowing.

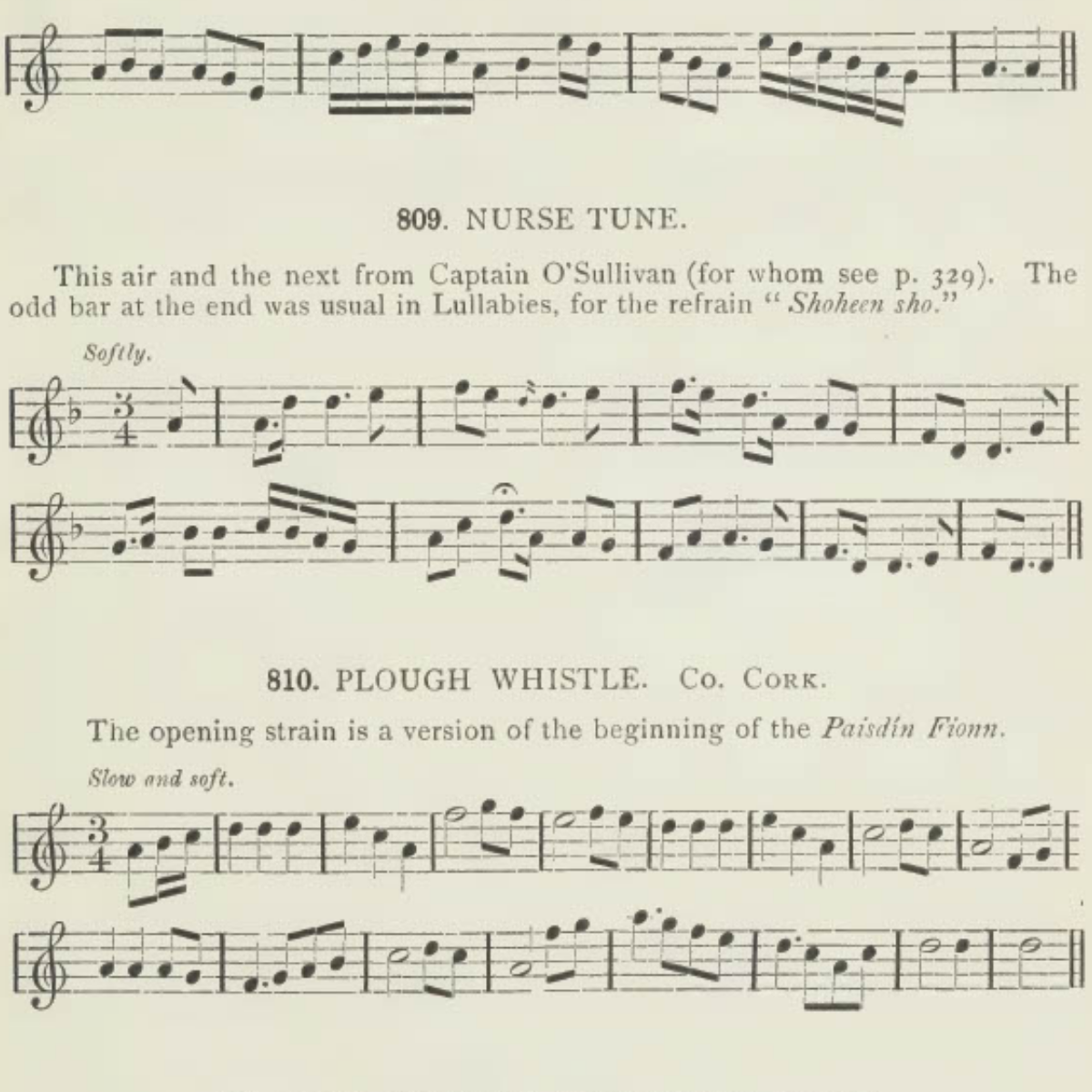

In A Social History of Ancient Ireland, Joyce relates how they were used during milking in Ireland and Scotland. He writes, “These milking-songs were slow and plaintive, something like the nurse-tunes, and had the effect of soothing the cows and of making them submit more gently to be milked.”

He also describes how when “… ploughmen were at their work, they whistled a peculiarly wild, slow, and sad strain, which had as powerful an effect in soothing the horses at their hard work as the milking-songs had on the cows.” I find this kind of lovely, the idea of using soothing tunes to encourage animals to help with work tasks.

On the Amgueddfa Cymru – Museum Wales website, I discovered a collection of folk songs with lyrics and recordings. The recordings are in Welsh, but you can toggle the lyrics between English and Cymraeg (Welsh) with the language choice at the top of the page. They include a work song that Welsh ox-drivers would use to gently “urge oxen at work.” If you’d like, you can listen to it here.

Group Dialogue Work Songs

Spinning, knitting, and sewing were tasks that were often performed in a group while gathering at one member’s home. In an earlier article, I explored the noson weu (knitting night), a social tradition in rural Wales that combined knitting, song, and story.

In Ireland, there was a similar tradition, which included the singing of dialogue songs by women while they spun, knit, or sewed. Essentially, the way the dialogue song worked was that one woman would begin a musical conversation, another woman would reply, and the rest of the group would provide a chorus. As the verses were often extemporaneous, the chorus section would give the two dialogue singers a moment to prepare their response.

The subject matter of these dialogue songs would often be in praise/dispraise of different young men. As you might think, the songs could get personal, but insults were taken in stride as part of the musical game.

In “Functions of Irish Song in the Nineteenth Century,” Breandán Ó Madagáin notes that these songs were meant to be fun, “relieving the monotony of the work.” And while they seem similar to waulking songs, they weren’t used so much to keep a rhythm as they were to help pass the time.

Lullabies and Faeries

Now, as you most likely know, I am a fan of faerie folklore. So it wouldn’t be a proper post if I didn’t include any faerie lore! 🙂 Needless to say, I was pleased to discover that not only were lullabies considered work songs, but in Ireland they might have also served a supernatural purpose. In “Functions of Irish Song in the Nineteenth Century,” Ó Madagáin explains:

Lullabies were commonly used in the nineteenth century and their obvious function is frequently referred to: Joyce had ‘seen children lulled to sleep hundreds of times with such lullabies.’ Internal evidence, however, may suggest that the lullaby had another function as well, of a supernatural nature. There is remarkably frequent reference in the extant lullabies to the world of the sí or fairy, and to the power of the ‘good people’ to abduct mortals, whether adult or infant.

He further explains that in some of the lullabies, there are lyrics that might be used to banish a faerie such as, “Gabh amach a bhóbabha [Get out fairy].” He also wonders if perhaps these types of lullabies were believed to serve as a charm to protect a child from faerie abduction.

Work Songs Helped to “Lighten the Labor” and Build Community

While work songs could have many functions, Ó Madagáin points out that the main purpose of work songs was to make work feel more cheerful, often by employing humor in the tune. It was an easy and fun way to bring amusement to daily chores and tasks.

Singing also helped members of a society to build community and enrich their social lives. Additionally, work songs offered individuals and groups an outlet for artistic expression and feelings of emotion while engaging with the necessary responsibilities of daily life.

I can see now why the nights when my daughter puts on a music playlist so that we can sing and dance while we wash dishes feel fun and lighter than when I’m washing them alone and in silence. Or when I meet other writers at a coffee shop that plays music I enjoy—it not only lightens the work, but it enables me to write in community.

I wish you a music-filled day! As ever, thank you for reading my blog. If you know someone fascinated by folklore, feel free to share this post with them.

Art credit (featured image): Two songs from Old Irish Folk Music and Songs: A Collection of 842 Irish Airs and Songs Hitherto Unpublished by P. W. Joyce. (The page has been cropped.) Public domain.

- Although the title of his book includes the phrase “Ancient Ireland,” this particular section on work songs makes references to the 1700-1800s. Also, this might be the longest book title I’ve ever come across, so I’ll use a shortened version going forward. ↩︎