When I began researching this topic, I initially planned to explore owl folklore as a way to discuss a folktale referenced by the character Ophelia in Shakespeare’s Hamlet. But once I started taking notes, I discovered that I what I wished to share with you would be too much for a single post. So I’ve decided on a two-month owl folklore theme. This month we’ll explore British folklore related to the owl and the story of Blodeuwedd. That way we’ll have better context for when we examine the folktale alluded to by Ophelia in next month’s post.

Roman Influence on Owl Folklore in Britain

Owl folklore in Britain seems to stem from Roman beliefs and literature. T. F. Thiselton Dyer, in his work Folk-Lore of Shakespeare, explains that from early on Roman writers depicted the owl as “a bird of ill-omen.” He gives several examples:

… Pliny [Pliny the Elder] tells us how, on one occasion, even Rome itself underwent a lustration, because one of them [an owl] strayed into the Capitol. He represents it also as a funereal bird, a monster of the night, the very abomination of human kind. Vergil [sic] describes its death-howl from the top of the temple by night, a circumstance introduced as a precursor of Dido’s death. Ovid, too, constantly speaks of this bird’s presence as an evil omen; ….

Thiselton Dyer speculates that the owl’s appearance, its sometimes unsettling calls, and nocturnal activity may have contributed to these beliefs. He also shares an extract from the Cambridge Latin Dictionary (published in 1594) that links the owl to folklore. For the Latin word strix, he quotes from the dictionary:

Strix, a scritche owle [screech-owl]; an unluckie kind of bird (as they of olde time said) which sucked out the blood of infants lying in their cradles; a witch, that changeth the favour of children; an hagge or fairie.

What an “unluckie” definition for the screech-owl! As a bird lover, it troubles me to think that owls were associated with bad luck, vampiric tendencies, witches, and faeries. But I do find the parenthetical aside of “as they of olde time said” amusing because here I am in 2025 reading this in a book written in 1884, which is referencing a dictionary entry from 1594, which is referring to “olde” times.

Owls Were Considered a Portent of Bad Luck and Death

The British owl folklore that emerged from these Roman beliefs was often linked to death portents and bad luck. An owl seen at a baby’s birth was thought to bring misfortune. Additionally, it was believed that owl calls heard near a house foretold ill luck or even death. In Welsh Folk-Lore: A Collection of the Folk-Tales and Legends of North Wales, Elias Owen shares that this belief has even made its way to rhyme:

Os y ddylluan ddaw i'r fro,

Lle byddo rhywun afiach

Dod yno i ddweyd y mae'n ddinâd,

Na chaiff adferiad mwyach.

If an owl comes to those parts,

Where some one sick is lying,

She comes to say without a doubt,

That that sick one is dying.

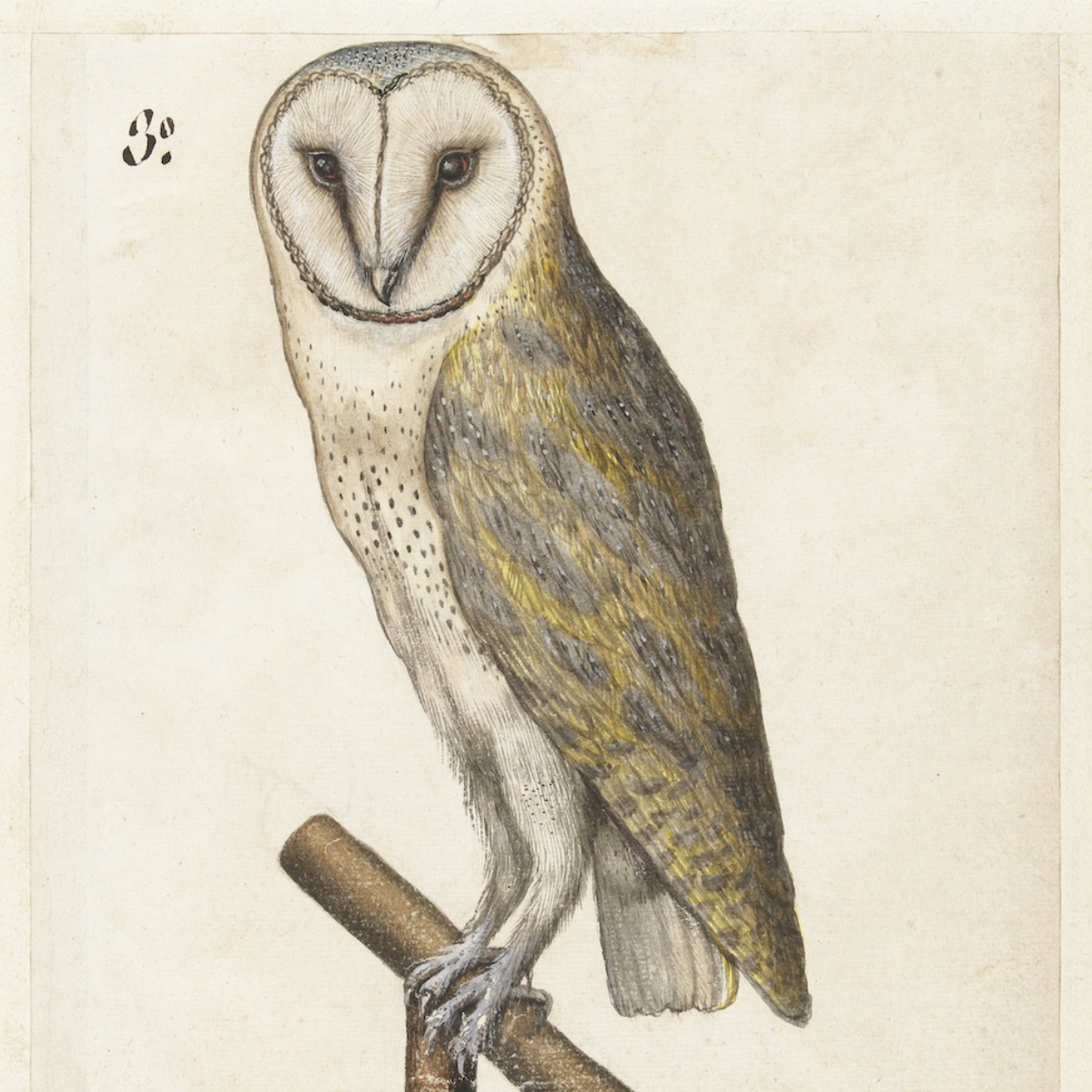

Most of the folklore I encountered linked the “dismal” call or screech of the owl to death portents. We have great horned owls in the area where I live, and their “hoo-h’HOO-hoo-hoo” call is fairly gentle. But the Woodland Trust’s article, “How to Identify UK Owl Calls” by Charlotte Varela, explains that “a barn owl call is a shrill screeching sound, which has earned the owl the nickname ‘screech owl.’” The post also includes audio of the barn owl if you’d like to hear its call.

Owls and Faeries

Owls were also connected to the faeries, as alluded to in the definition of the Latin word strix. This association seems quite strong in Welsh folklore. Similar to strix, the Welsh word ŵyll reveals ties to owls and faerie folklore. In the thesis “Y Tylwyth Teg: An Analysis of a Literary Motif,” Angelika Heike Rüdiger offers a mostly translated definition of ŵyll from Geiriadur Prifysgol Cymru (the University of Wales Dictionary of the Welsh Language). I have added a few definitions in brackets to further clarify. Rüdiger writes:

Geiriadur Prifysgol Cymru (GPC) offers ‘ellyll [goblin, elf, faerie], gwrach (‘witch’), un o’r tylwyth teg’ [one of the faeries], but also ‘tylluan (wen)’ (‘(screech) owl’) and ‘drychiolaeth’ (‘apparition, ghost, spectre, phantom’) as synonyms of ‘ŵyll’.

In this we can see that the word ŵyll applies to both the screech owl and denizens of faerie, as well as to the supernatural. Rüdiger also points out that the screech owl is linked to Gwyn ap Nudd (the king of the faeries) by the medieval Welsh poet, Dafydd ap Gwilym:

In many of his poems Dafydd ap Gwilym talks in a jocular way about situations which are inconvenient for him, and in these poems he refers to Annwn [the Welsh otherworld] or Gwyn ap Nudd, or the Welsh fairies as acting mischievously. In ‘Y Dylluan’ (‘The Owl’), an owl keeps him from sleeping by hooting and screeching at night, so that Dafydd says that ‘Edn i Wyn ap Nudd ydiw’ (‘it is Gwyn ap Nudd’s bird’) ….

I read an English translation of this poem through the DafyddApGwilym.net website (Swansea University), and it is a scathing portrayal of the the poor owl. But perhaps it was meant to be tongue-in-cheek, like a roast? In addition to the Gwyn ap Nudd reference, the poem also includes the line: “Annos cŵn y nos a wna” (“it [the owl] incites the dogs of the night”). The website offers a note on this stating that it might be a reference to the dogs of Annwn (Cŵn Annwn), and in this way, further links the owl to the otherworld. (You can learn more about Cŵn Annwn in this earlier post of mine.)

Blodeuwedd: A Maiden Transformed Into an Owl

In “The Fourth Branch of the Mabinogi” (a tale in the Mabinogion), we meet a beautiful maiden originally named Blodeuedd. But she was not an ordinary maiden—she was created from flowers to be the wife of Lleu by two men with magic: Math and Gwydion. In Sioned Davies’ translation of the Mabinogion, it reads:

Then they [Math and Gwydion] took the flowers of the oak, and the flowers of the broom, and the flowers of the meadowsweet, and from those they conjured up the fairest and most beautiful maiden that anyone had ever seen. And they baptized her in the way they did at that time, and named her Blodeuedd [meaning “flowers”].

But Blodeuedd did not seem to love her husband, Lleu. Instead, she fell for another man, and together they planned the death of her husband. When her lover struck Lleu with a poisoned spear, “Lleu flew up in the form of an eagle and gave a horrible scream.” Gwydion punished Blodeuedd by transforming her into an owl and declared:

“And because of the shame you have brought upon Lleu Llaw Gyffes, you will never dare show your face in daylight for fear of all the birds. And all the birds will be hostile towards you. And it shall be in their nature to strike you and molest you wherever they find you. You shall not lose your name, however, but shall always be called Blodeuwedd.”

In a note, Davies explains that the addition of the “w” in her name changes the meaning from “Blodeuedd (‘flowers’) to Blodeuwedd (‘flower-face’), to reflect the image of the owl.”

Blodeuwedd’s transformation into an owl links the bird to death once more. John Rhŷs, in Celtic Folklore: Welsh and Manx, explains that for both Blodeuwedd and Lleu, when they are changed into birds, it is considered to be their deaths. Through a lengthy philosophic discourse Rhŷs describes several stories of shape-shifting characters and explores some druidic beliefs, then seems to reach the following conclusion:

So we may perhaps venture to suppose that the druids … believed in the transmigration of souls, including that from the human to an animal form and the reverse.

In his book, Elias Owen also explores the idea of the transmigration of souls (the concept that after death the soul passes into another being, including animals). He notes that tales where people are transformed into animals “… prove that people believed that such transitions were in life possible, and they had only to go a step further and apply the same faith to the soul, and we arrive at the transmigration of souls.”

While the idea of transforming into a new form is quite common in folktales, I wasn’t able to determine definitively if it indicated a belief in the transmigration of souls. Perhaps these types stories instead reveal an interest in characters who endured regardless of form. It seems open to interpretation.

Blodeuwedd’s transformation into an owl has recently been beautifully illustrated by Adam Simpson as part of a new set of commemorative stamps (Myths and Legends) issued by the Royal Mail. Gareth Bradwick, a Welsh newsletter writer I know, brought this article to my attention, which has some great photographs of the collection. Thanks, Gareth! (His newsletter, Popped, explores the history and legacy of film.)

I hope you enjoyed this month’s post! Learning about British owl folklore, Blodeuwedd’s story, and the idea of transformation should set us up nicely for next month’s topic: a folktale referenced by the character Ophelia in Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

As ever, thank you for reading my blog. If you know someone fascinated by folklore and folktales, feel free to share this post with them. Thanks!

Art credit (featured image): Barn Owl via Public Domain Image Archive, licensed under CC0